Staff records can be classified into three categories (well in the L&SWR’s case at least). Firstly, it is important to note that within all 19th Century railway companies there were two employment streams, the clerical and secondary labour markets. Those clerks in the clerical labour market had to go pass rigorous entrance requirements and tests, but once employed enjoyed good promotional prospects, salaries that were paid to them monthly and job security. Indeed, many clerks became senior managers. The secondary labour market encompassed all other staff. Most were paid weekly, had poorer wages than clerks and had low job security. Thus, it is only natural that the staff records of these two employee groups are different in character. While in both cases individuals’ details were either recorded on a full or half page of a book, the clerical staff’s details were usually recorded in a larger book, but, surprisingly, had fewer forms of information within. Lastly, in addition to these records, there were the ‘registers of workmen’ that recorded the details of many individuals over two pages.

Clerical staff registers, in the case of the L&SWR at least, have a separate index which is very handy when looking an individual up. Five pieces of information were recorded on the clerical staff registers held at the National Archives. These were the age of the individual when they started their employment, date of entry into the service, who nominated them for a clerical post, any ‘positions and removals or promotions’ and ‘reports and complains.’

A couple of things stand out about from these records that should be noted. The individual who nominated them for a clerical position was usually either a senior manager within the company or a director. However, ordinarily they would have been written to by a ‘respected’ individual who knew the prospective clerk, for example a school teacher, religious figure or a local dignitary. In the section recording ‘positions and removals or promotions’ was recorded all the details of an individuals’ pay at certain points and the length of time they spent at different locations. On many occasions, their post-employment details, such as their pension and date of death were also recorded. Lastly, the records detail any ‘reports and complaints.’ This encompassed any time a clerk did something exemplary in the line of duty, or did something which would warrant punishment. Punishments included fines, demotion or, in worst case scenarios, dismissal. For example, in February 1892 T.H. Jebbitt, the Agent at Basingstoke, was called upon to resign because of ‘irregularities in various cash matters.’ (shown below) What these irregularities were is not noted in his staff record, but it is at the point that the diligent researcher would seek out the Traffic Committee minute book to find out.

The staff records of those in the secondary labour market usually have more information contained within them. Unfortunately, despite this bonus, in the case of the L&SWR there is no index which means that finding an individual is a laborious task involving searching through every record. What’s more, in the case of the L&SWR many staff records are missing, and only some individual personnel files from the Traffic Department have survived. The information for which there spaces on the record are the staff member’s date of birth, height, the ‘number of the testimonial,’ address when appointed, who recommended them, their date and place of appointment, grade, starting wage, marital status, any remarks, whether they passed the eyesight test and their promotions or wage increases.

Clearly, the larger amount of information recorded was because many in the secondary labour market, such as cleaners, platelayers or porters, were doing more arduous and labour-intensive work. Thus, more details furnished as to their physical appearance and attributes so that their suitability for the job could be assessed. However, what has been noticed is that on many occasions not all the information was filled in, presumably because of the nature of individuals’ jobs. For example, Mrs Watkin (below) was appointed as a waiting room attendant and because the job was not that labour-intensive many of the details have not been filled in.

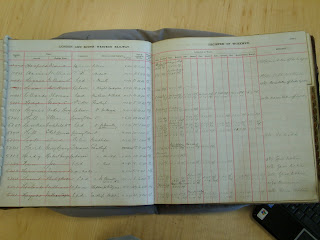

The last form of employee information was the staff registers that listed the details of many L&SWR employees consecutively (below). However, because so many individuals were listed on two pages the information furnished is not as detailed as in individual staff records. However, a positive thing about the staff registers is that they usually had an index at the front from which individual employees could be found within them. As far as the L&SWR is concerned, only staff registers from the Locomotive Department have survived at the National Archives and the Hampshire Record Office. They record, the employees’ ‘register no.’ (which presumably linked to an actual person’s record), their names, their occupation, where they were employed, the date they entered the service, their starting wage, any wage increases and lastly any remarks. Yet, what the registers do not record, as far as can be seen, are any promotions, rewards or disciplinary actions. Thus, these can be somewhat frustrating files for the historian because of the limited information contained within them

It should be recognised that what I have detailed here only applies only to the L&SWR, and the other railway companies may have set out and organised their staff records differently. Irrespective of this, the staff records of railway company employees are a really useful source for all historians, even if they can be frustrating a lot of the time.

No comments:

Post a Comment